Why bombers on WWII’s legendary ‘Doolittle Raid’ had broomsticks instead of tail guns

Imagine volunteering for this: you and 79 other soldiers will fly 16 bombers that have never flown in combat before off an aircraft carrier not built to launch those bombers, fly those bombers over hundreds of miles of open ocean, race over enemy territory at treetop level, drop bombs, then eject or land a few hundred miles later and be either captured, executed or isolated far from home with no guarantee of return.

Oh, and by the way, you can’t take the bomber’s usual load of machine guns on the flight because it will weigh down the aircraft. Instead, take these painted broomstick handles and install them in the back of the plane. That should frighten enemy fighters from a distance.

It does not sound fun, but that was exactly the job description of the 80 Army aviators who took part in the Doolittle Raid, the legendary mission to strike back at Japan shortly after the attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The raid, which historians credit with playing a key role in helping the Allies win World War II, took place exactly 80 years ago today.

In the months after Pearl Harbor, the Japanese army took a staggering number of islands across the Pacific, including large American bases in the Philippines. President Franklin Roosevelt wanted bombs dropped on Japan as soon as possible to both boost morale at home and weaken morale in Japan. Though Roosevelt wanted bombs, the plan to accomplish his mission was thought up by a Navy submariner, Capt. Francis Low, who believed medium-sized Army bombers could take off from a Navy aircraft carrier. It was possible using modified B-25 bombers, but it would take a daring pilot to pull it off. Enter Lt. Col. James Doolittle, a “noted racing and stunt pilot,” according to HistoryNet.

“Jimmy Doolittle, a very energetic man, decided that the B-25 crews would consist of five men: pilot, copilot, navigator, bombardier and engineer-gunner,” wrote HistoryNet. “To preserve secrecy, Doolittle personally began making all the arrangements for the training and special equipment without revealing why he wanted things done.”

Subscribe to Task & Purpose Today. Get the latest in military news, entertainment, and gear in your inbox daily.

To maintain secrecy, Doolittle initially did not even share the details of the high-risk mission when he called for volunteers to fly it. He said the mission would be “exceptionally dangerous,” but could say no more, Doolittle wrote alongside historian Caroll Glines in their book “I Could Never Be So Lucky Again.”

The lack of details was no obstacle for the volunteers, who no doubt were itching to give Imperial Japan a black eye in return for attacking Pearl Harbor, where 2,300 Americans were killed, and 18 ships sunk or run aground. Twenty-four aircraft and their crews gathered at Eglin Field, Florida to practice cross-country flying, night flying, navigation and the one-of-a-kind task of taking off from an aircraft carrier.

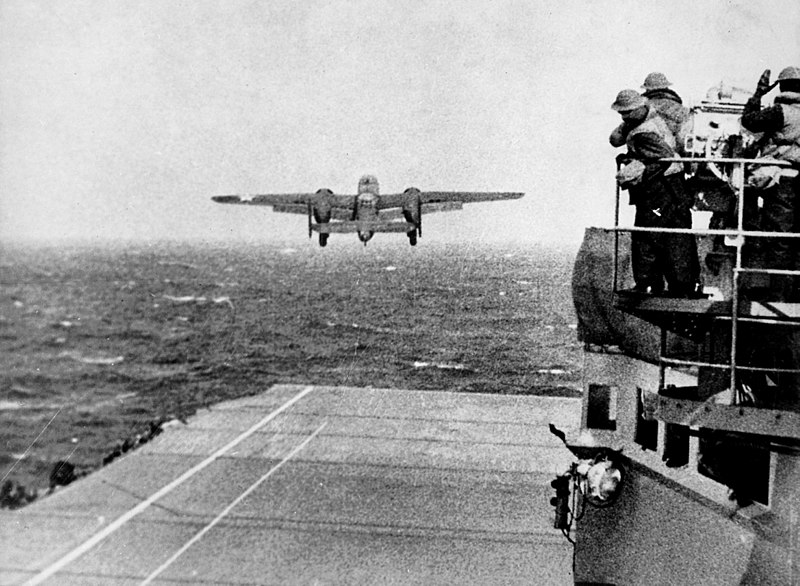

“With everything not deemed essential stripped from the planes, [USS] Hornet loaded 16 B-25s (all that could be shipped) on board at Alameda (31 March–1 April 1942) and sailed” to meet its escort, the carrier USS Enterprise, wrote the Naval History and Heritage Command online.

To make the long journey, the B-25 bombers were heavily modified with extra fuel tanks (the fuel capacity nearly doubled from 646 gallons to 1,140), along with the removal of the heavy radio and several machine gun turrets, the replacement of the heavy, top-secret Norden bombsight with a 20 cent aluminum version. Broomstick handles were also painted black and installed on the back of the airplane so that it would look to enemy fighter pilots as if the bombers had tail guns, according to HistoryNet. There was disagreement among sources about whether the B-25Bs used in the raid were initially built with actual tail guns or not.

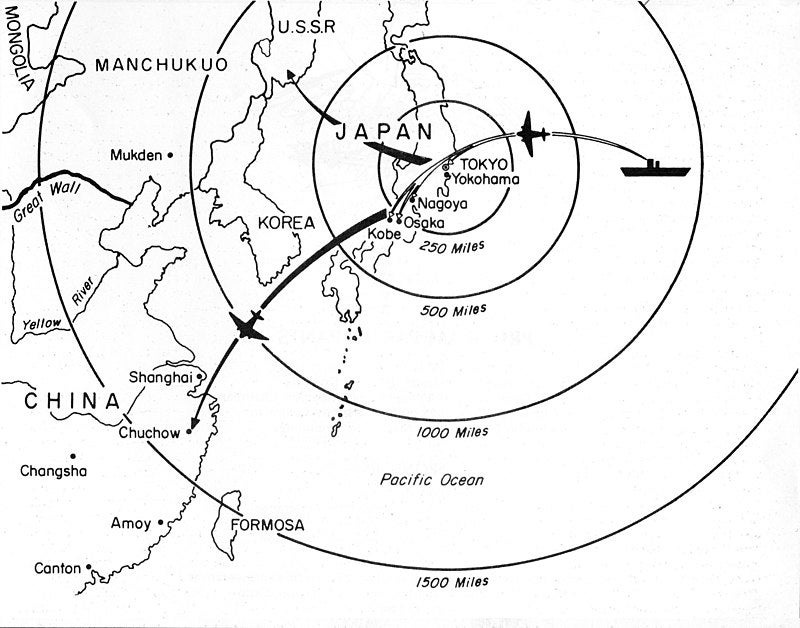

The plan was to launch the bombers about 600 miles east of Tokyo, but fate had other plans. On the morning of April 18, the Navy detected two Japanese picket boats which threatened to raise an alarm over the American task force. Keep in mind that the two aircraft carriers of Task Force 16 represented a crucial chunk of American firepower in the entire Pacific. If a stray Japanese torpedo sunk one or both of them, it would be a colossal strategic blow to U.S. prospects in the war. With that risk in mind, Vice Adm. William Halsey Jr. ordered the bombers to launch earlier than planned, more than 820 miles from Tokyo.

“Launch planes. To Col. Doolittle and gallant command, good luck and God bless you,” Halsey messaged the aviators, according to Encyclopedia Britannica.

Though the seas were rough that day, all 16 B-25s took off without mishap and were airborne by around 9:20 a.m. The plan was to fly over the Pacific and drop high explosive and incendiary bombs on military targets in Tokyo, Yokosuka, Yokohama, Kobe, and Nagoya, before crossing the East China Sea and landing at Chinese airfields, according to the Naval History and Heritage Command. The element of surprise paid off, and the 16 aircraft met “negligible opposition” on their way to the targets.

“Shortly after noon, Tokyo time, Doolittle called for bomb doors open, and Sergeant Fred Braemer sighted down the 20- cent bombsight and triggered off four incendiaries into the capital city’s factory area,” wrote HistoryNet.

Fourteen other crews also hit their targets, but one bomber came under attack by fighters and dropped its bombs in Tokyo Bay. Nearly all the crews bailed out over China when their fuel ran out, though one landed in the Soviet Union. Despite the mission’s dangerous premise, 14 complete crews survived and managed to return to U.S. forces before the end of the war. One soldier was killed while trying to bail out of a B-25, and two crews were captured by Japanese forces in China. Of those, three soldiers were executed while a fourth died of dysentery, according to Encyclopedia Britannica.

Though they inflicted little actual damage on their targets, the sacrifice of the Doolittle Raiders proved to be one of the turning points of the war.

“[T]he effect of the air raid on the Japanese capital itself was enormous,” wrote Naval History and Heritage Command. “Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku’s fear of a U.S. carrier strike against the homeland, deemed ‘unreasonable’ by the Naval General Staff, had occurred unimpeded.”

Determined to prevent similar attacks in the future, the Japanese navy later launched an attack at the U.S. naval base at Midway, where the U.S. navy would emerge triumphant after inflicting unsustainable losses on their adversary.

“Jimmy Doolittle’s famous air raid against Japan marked the beginning of the turnaround toward victory for America and her allies in World War II,” wrote HistoryNet.

Update: This story was updated in light of conflicting information over whether the B-25B bombers used in the raid were built with tail guns.

What’s new on Task & Purpose

- The Marine Corps’ culture has to change

- This Army ‘Best Ranger’ competitor showed soldier ingenuity that had instructors face-palming

- How an airman fought off a grizzly bear in Alaska

- Tom Hanks to continue his absolute domination of World War II entertainment

- A soldier was left to die alone in his barracks for 5 days. His family wants to know why

Want to write for Task & Purpose? Click here. Or check out the latest stories on our homepage.

The post Why bombers on WWII’s legendary ‘Doolittle Raid’ had broomsticks instead of tail guns appeared first on Task & Purpose.